Blabber n' Smoke

Words about film, music, et cetera by Shaun Brady.

Tuesday, December 01, 2015

Robert Altman Study Part 21: Buffalo Bill and the Indians & 3 Women

If Buffalo Bill and the Indians or Sitting Bull's History Lesson is largely regarded as a failure, it's mostly because it had to follow Nashville, revisiting some of the same themes with less ambition and success. Again Altman is satirizing the American tendency to blur the lines between politics and celebrity, this time coinciding with the country's bicentennial year and skewering its penchant for mythologizing. All the same, it's not an uninteresting film (none of Altman's films, even his worst, are) and still feels relevant in an election year where no fact can stand in the face of bravado myths. "Truth is whatever gets the loudest applause," Paul Newman's Buffalo Bill Cody says at one point, and nothing feels more morbidly accurate while watching presidential debates. Still, the film tends to hammer home a single point and is uneven - the noble indians are stereotypes just as much as the scalping savages in the Wild West Show, and the scene where Sitting Bull wins over a raucous crowd with his quiet dignity is not only unbelievable but seems to let Bill's (and America's) audiences off the hook too easily.

3 Women is the most successful of Altman's "dream films," following That Cold Day in the Park and Images in its depiction of female characters suffering psychotic breaks and fracturing in mirrored surfaces. While those earlier films seem disconnected from the director's more male-centered and ensemble films, 3 Women hews a little closer in its wry satirical sense and its sense of women forming armored personalities in the face of their profligate men. Shelley Duvall's Millie is one of his (and her) most striking characters, a creation of self-help media whose insecurity is so severe that it curves completely around to become impenetrable self-confidence. It is in the end a mood piece, one that manages to be unsettling long before anything actually strange happens, and while less inscrutable than some critics claim is still an admirably ambiguous, impressionistic portrait of fluid identities. Every single person in the film seems to be a shadow of someone else: Millie of some idealized '70s "modern woman," Pinky (Sissy Spacek) of Millie. But even peripherally there are the twins and another pair of women always seen together at the geriatric spa where Pinky and Millie work; and Edgar (Robert Fortier), once Hugh O'Brian's stunt double. Willie (Janice Rule) is a singular figure, but barely more than an apparition, always silent, alone, and painting her strange, evocative murals.

Thursday, November 12, 2015

Robert Altman Study Part 20: California Split & Nashville

I've fallen a bit behind on these, so just brief notes for now...

Probably my favorite of Altman's films, California Split is where the director truly finds his ideal comedic rhythm. Previous films had veered too strongly toward juvenile sneering (M*A*S*H) or scattershot farce (Brewster McCloud), but in this tale of sad sack gamblers the laughs are fully integrated into Altman's spontaneity-embracing style.

Given Altman's own penchant for gambling, the temptation is to assume autobiographical intent in the film. It's there, certainly, though perhaps not in the way one might think. California Split is an analogue for Altman the filmmaker, not the card player or dice roller. As I've mentioned before, his movies are gambles; where he seemed to be happiest was on set, embracing the whim of the moment. How they came together in the end appears to be secondary. It's the same sobering realization that George Segal's Bill has at the end of the film, where he's confronted with the fact that his jackpot doesn't sate his urge to gamble. It's the thrill of the risk that appeals, not the payoff.

Nashville is typically acclaimed as Altman's masterpiece, and it's hard to argue that fact. It's one of the best films ever made about the American psyche, and feels as sadly relevant today as it did in 1975 - maybe more so, as the lines between celebrity and politicians are ever more blurred, especially in the age of a looming Trump presidency, and the desperation for fame is at a fever pitch given the newfound ease of "celebrity" in the modern day. Altman's masterful juggling of a true ensemble cast gives the illusion of being about nothing in particular while making profound points from the accumulation of details. Different things stand out with every viewing; this last time I was more struck than ever by the subtle grace of Lily Tomlin's performance, which is deeply moving without spelling out anything. Her loneliness, intelligence, dedication to family and need for love - but not fantasy, as in her brilliantly mature leave-taking of Keith Carradine's self-loathing rock star shows - are all communicated but never advertised.

Monday, August 31, 2015

Robert Altman Study Part 19: Thieves Like Us

After all the talk in my last several entries about Altman's freewheeling approach to adaptation comes Thieves Like Us, which is surprisingly faithful to its source material - certainly more so than Nicholas Ray's 1948 version, They Live By Night. The latter is by no means a severe departure, but it updates the 1937 Depression-set novel by a decade and makes its leads far more glamorous than the novel or Altman's take would. It's also required by the Production Code to marry Bowie and Keechie before they can run off together, though to Ray's credit this leads to one of the film's best inventions, the shyster minister played by the great character actor Ian Wolfe.

Shot by French cinematographer Jean Boffety after Long Goodbye co-star Mark Rydell absconded with much of Altman's crew to make Cinderella Liberty, Thieves Like Us imbues its hardscrabble Mississippi with a misty lushness, imposing both a gauzy nostalgia as well as a bleary melancholy over the landscape. It's here that Altman offers the most concise and focused take on a theme that runs as an undercurrent through so much of his work: the idea that men are dreamers whose pursuit of unrealistic goals dooms them, and that women are forced to be more pragmatic and perseverant in order to stay the course that their men keep insisting on deviating from. The concept was also at the core of McCabe and Mrs. Miller and would recur immediately (though in less balanced form) in California Split. To some extent it also explains the director's uncanny female-centered film, set in worlds that become skewed when women can't even hold the center.

The men here are T-Dub (Bert Remsen) and Chickamaw (John Shuck), two seasoned bank robbers, who escape from prison along with the inexperienced Bowie (Keith Carradine). Their female counterparts are Mattie (Louise Fletcher), T-Dub's taciturn sister-in-law, forced to raise her children alone since her husband is serving time; and Keechie, perhaps the most revealing performance by the always-open Shelley Duvall, a sheltered girl who falls immediately in love with the puppy dog-like Bowie, but has more common sense about the dangers of his life of crime than he does.

In many ways the anti-Bonnie and Clyde, Thieves Like Us begins as another rollicking tale of Depression-era bank robbers, less altruistic Robin Hoods who envy bankers and lawyers who "rob people with their brains instead of guns." But it turns darker as the desperation and paranoia of the men escalate, allowing Shuck a stunning turn as the increasingly drunk, disturbed, and violent Chickamaw, his bulldog features turned rabid in a way that none of his genial earlier roles for Altman even hinted at. Remsen's T-Dub is another in the filmmaker's rogues' gallery of fast talking con men whose aimless, seat-of-their-pants actions never quite live up to their optimistic bragadoccio.

Altman's innovative but only occasionally effective use of '30s radio shows in lieu of score speaks to the romanticization of thieves and their derring-do at a time when most in the country were suffering financial hardship. But the running thread of Coca-Cola ads - on every gas station, corner store, and even prison - hint at the encroaching consumer culture that would soon overtake the country.

The one major change that Altman and screenwriter Joan Tewkesbury make to the novel - and that Ray made as well - is to allow Keechie to survive Bowie's brutal gunning down by police. In this case, she's glimpsed setting out on her own on a train to wherever, about to give birth to a child she determinedly won't name after its father, becoming as hardened as Mattie in order to survive.

Thursday, August 06, 2015

Robert Altman Study Part 18: The Long Goodbye

From the western, Altman moved on to film noir with similar intent: subverting expectations. Not so much subverting genre; though his cinematic reinventions and their timing aligned him with the film school brat generation, he's not exactly of them. He's almost a generation older, for one; for another, he's less interested in meta explorations than in using generic conventions to disregard storytelling. The Long Goodbye, despite its undermining of Bogart's Marlowe ideal, isn't about undermining noir. It's about twisting the expectations of noir to comment on the shifting mores of the day.

Altman referred to Elliott Gould's portrayal of Raymond Chandler's iconic private eye as "Rip Van Marlowe." The idea was to take the '50s-era detective and drop him into the world of 1973. And Gould's Marlowe does feel like a man out of time: he wears a suit and tie, however rumpled, while his neighbors practice topless yoga. He's the only character who smokes in this health-conscious era, striking his matches on whatever available surface. And he has a firm sense of morality and justice at a time when such notions feel quaint and outdated.

All of which makes him a sucker rather than a hero, a notion that offended Chandler devotees. But it also gets paid off in his killing of Terry Lennox, a drastic departure from the source novel that originated not with Altman but with screenwriter Leigh Brackett but which Altman made a contractual obligation of his taking on the film. Everyone in the film except for Marlowe is absorbed in their own self-interest, down to his picky cat, who disappears when Marlowe attempts to pass off a non-approved brand of cat food.

Once again Altman thrives when he can push story to the background and focus on details. The big reveal of Lennox's betrayal is relegated to a mumbled voiceover running against sunset shots of Mexican cityscapes. There is an utter disregard for the "mystery" at the heart of the story, which is fundamentally changed from Chandler's book, though Chandler himself preferred language to narrative sense. Brackett's final scene, leading up to Lennox's shooting, is a fairly typical sum-up of the details. In Altman's hands, most of this dialogue is jettisoned - just enough remains to make some sense of the plot, but what's important is Gould's sense of resigned indignation.

Altman reportedly insisted that key cast and crew read Raymond Chandler Speaking, a collection of correspondence and essays in which the author propounds on the detective story, writing, and cats - a clue to where that opening scene comes from. Much of the film's attitude can be found in these pages; even if Chandler might not have approved of the changes made, as he rarely did in the adaptations of his books, he'd have to admit to a shared philosophy. Even an offhand description of Marlowe striking his matches on any convenient surface emerges in the film's depiction of the character, a trait not mentioned explicitly in any of the novels or stories.

Thursday, July 30, 2015

Robert Altman Study Part 17: Images

The second of Altman's "disturbed women" films is a slight improvement on That Cold Day in the Park, but a definite disappointment coming between the high points of McCabe & Mrs. Miller and The Long Goodbye. At this stage, he worked best when adapting strong stories by other authors rather than devising original stories.

Images is simply too schematic and obvious in its attempt at dream-like imagery. The near-constant use of fragmented and distorted reflections weighs down what is already a thin attempt at psychologizing, which is then summed up by a too-literal finale. Essentially the story of a woman haunted by jealousy brought on by her own affairs, Images pathologizes this less-than-compelling dilemma to the point of schizophrenia. We're trapped in the head of Susannah York's character, but find nothing of much interest there in either her confusions or revelations.

It's a sometimes lovely (especially in its use of the Irish countryside, which is nonetheless incidental to the film itself) and well-acted movie, but amounts to a pile-up of affectations - there's the round-robin name-swapping, with each of the lead actors playing a character with one of their co-stars' names (Rene Auberjonois as Hugh, Hugh Millais as Marcel, Marcel Bozzuffi as Rene). Then there's the interstitial readings from York's own then-in-progress children's book In Search of Unicorns that brings a sense of fantasy to the proceedings but doesn't align particularly well with the story being told. It's one of those gambles that Altman loved to take, but one of the more-rare-than-not cases where it doesn't pay off.

(I grabbed a copy of the book, incidentally, which is itself a fairly vague and anecdotal account of fantasy creatures and their battle against an evil nuisance, so maybe there was something in the air.)

Robert Altman Study Part 16: McCabe & Mrs. Miller

Altman's first masterpiece arrived via this poetic western, an unlikely adaptation of Edmund Naughton's 1959 novel. Again as I proceed chronologically through his work, I'm gaining a newfound and deep appreciation for Altman's skills as an interpreter of other people's work. Especially in the early going, his best films are those which take their spine from a solid but unremarkable narrative and discard it at will - to paraphrase what Altman himself says in the fine commentary track in the McCabe DVD (which he shares with producer David Foster, a wise move given the director's penchant to lapse into long silences on these tracks), he uses stories and genres with which audiences are already intimately familiar so that he can ignore the narrative to focus on details "in the corners." That would change somewhat when he started to create original films that focused more on setting than story, as with California Split and Nashville.

McCabe is the perfect example - a lone gunman rides into town, sets up a card table and eventually builds a small-time back-woods empire with gambling and prostitution, attracts unwanted attention from corporate mining interests, and has to face down the company's gunmen when he refuses to sell out. Altman finds his points of interest not in this oft-told tale but in the grubby historic details, the cutting down of his protagonist from the western hero to a self-interested braggart in over his head, the never-quite love story between the oblivious gambler and the opium-addicted madame.

Again, it's the deviations from the source material, many of which aren't in Brian McKay's script, that are telling. In both Naughton's novel and the screenplay, McCabe has earned his reputation as a gunfighter honestly, having shot a man in a gambling dispute. Altman strongly suggests that this event never happens, that it's a rumor that McCabe finds useful but has no basis in fact. The lawyer that McCabe sees in Bearpaw to attempt to fight the corporation is a kindly old man with a futile desire to fight the system until Altman transforms him into a glib and facetious politician of a type familiar to early-70s audiences. Finally, McCabe dies in all versions, but the written versions have Mrs. Miller cradling him as he expires, then shooting his weasel of a rival, Sheehan, for some measure of revenge. Altman changes this to the striking and unforgettable image of Julie Christie losing herself in an opium haze, resigned to the harsh realities of her position and escaping to another world in a piece of pottery.

Ultimately, in Altman's hands McCabe becomes another battle (lost, as usual) between the individual and society. As Warren Beatty's McCabe battles for his life, the community which he in large part has attracted to the growing town of Presbyterian Church bands together to fight a fire in the empty church which none of them have to this point stepped foot in - a sign of the civilizing changes to come, which almost necessitate that determined individuals be wiped clean. It's a cynical if well-supported examination of modern corporate culture, told in a gorgeously non-linear way.

The film is brilliant in its visuals alone. Altman and cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond achieved a nostalgic sepia tone by taking the risky step of flashing the film (exposing it to light after shooting in controlled situations), while the director takes full advantage of the severe winter landscapes offered to him by the Vancouver wilderness. Most importantly, he conjures a true sense of burgeoning community by building the town as he shoots the story in sequence, with production designer Leon Ericksen's incredibly detailed set coming to life in time with the film itself.

Monday, June 08, 2015

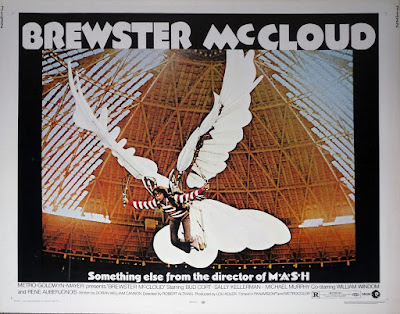

Robert Altman Study Part 15: Brewster McCloud

Not that Altman can be blamed - Cannon's script for Brewster McLeod's Flying Machine is one-note, mean-spirited, and largely pointless. Living in a Manhattan apartment rather than the Houston Astrodome, Cannon's Brewster is a conniving killer obsessed with flight, whose thoughts are heard almost constantly through voice-over. He has two lovers who for whatever reason throw themselves at him while abiding his abuse - a Puerto Rican caricature named Manessa and a nurturing older woman named Louise, who would become Sally Kellerman's de-winged Fairy Birdmother in the film version. He later meets a childhood sweetheart named Susanne, who would be transformed into Shelley Duvall's free-spirited love interest. This Brewster gleefully kills a series of rivals in the screenplay, the deaths finally catching up to him just as he's ready to launch into flight from Eero Saarinen's TWA Flight Center.

Then-film student C. Kirk McLelland hung around the Houston set of Brewster McCloud and published his journal as On Making a Movie: Brewster McCloud, which also contained the shooting script (essentially a shot-by-shot transcription of the finished film) and Cannon's screenplay. McLelland, despite a raft of factual inaccuracies and youthful egotism, captures the loose, unruly atmosphere of the shoot, which fully translates into the on-screen action. Altman has called his films "caprices" in interviews, and nowhere is that spirit more evident than in Brewster McCloud.

If the end result isn't entirely successful, it is in some ways the ultimate expression of Altman's gambling spirit. Each day's filming seems guided by the whim of the moment, a willingness to roll the dice on every wild idea and see what happens. If the director worked more like Mike Leigh, taking the time to take those chances for an extended period before the cameras roll, the end result might be more cohesive - but would lack Altman's seat-of-the-pants spirit.

At times the film works beautifully, most notably in Brewster's final flight in designer Leon Erickson's fantastic wing contraption, a breathtaking moment thrillingly shot and edited. Unlike Cannon's tale of a hands-on murderer, Altman's more elliptical approach is far more intriguing, with all the killings happening offscreen, heralded by birdshit hitting the victims, and the culprit left vague - is Brewster committing the crimes or is Louise - or the target-shitting raven? Does Louise even exist, or is she simply some Oedipal projection of Brewster's?

Other aspects suffer from the ever-changing script process. Most glaring is Lt. Frank Shaft's suicide, which comes from nowhere, matters little, and does nothing that Michael Murphy's already deadpan parody of Steve McQueen's Bullitt hasn't already accomplished. Far too much time is spent on the squabbles between opposing factions in the police and politics, which spatters birdshit on low-hanging fruit.

The two halves of the film, which come together in a freewheeling car chase, are thus somewhat at odds with each other, but each adds up to what is essentially a critique of the power structure and its squashing of non-conformity. By relegating the murders to offscreen action and only showing the victims - each venal, corrupt, and largely racist - taking a hit of flyby excrement, Altman suggests that these powerful people deserve to be up-ended by a dreamer and his work.

Still, a line from René Auberjonois' bird-man lecturer tips Altman's hat: "We will... hope that we draw no conclusions," he says regarding his intention to speak on the similarities between birds and men. "Elsewise the subject shall cease to fascinate and, alas, another dream would be lost." Nothing could better sum up Altman's approach, which merrily sacrifices comprehension for the pursuit of the dream.

Friday, June 05, 2015

Robert Altman Study Part 14: M*A*S*H

Most of the basic scenes that would end up in Altman's M*A*S*H are already there in the novel. But in Ring Lardner's script they're shaped and streamlined, and most importantly given a more irreverent twist. Hornberger reportedly never intended any anti-establishment criticism in his writing; that tone is unmistakable in Lardner's script. There's also a necessary economy, as in the character of Maj. Frank Burns: in the novel Burns is a blowhard and an incompetent surgeon who shifts blame for his own failings, as in the film. But the religious zealot who originally lives in the Swamp is a completely different character, brought up and dismissed within the space of a chapter - something that happens quite a bit. Every one of Hornberger's points seems to require a new character to be introduced and then shuffled off.

Altman then takes the script and breathes an entirely different life into it. Lardner had a longstanding grudge against the director over his "trashing" of the screenplay, ironically as it turns out given his Oscar win. That accusation turns out to be largely misjudged (unlike the case of Brewster McCloud), as most of Lardner's script is intact. It's simply not pristine, layered on top of itself, buried in the background or under a haze of anarchic slapstick, as Altman finds his ramshackle comic voice at last. More interested in making a case against Vietnam than in filming a comedy about Korea, Altman turns Donald Sutherland and Elliott Gould into a counter-culture Marx Brothers, with this unspecified war in Asia a real-life, blood-and-guts Duck Soup.

What matters in the case of the film is less the dialogue, which Altman famously piles up in a cacophony of mumbling and simultaneous conversation; but the messy atmosphere, a no-rules hothouse where juvenile behavior is the only possible response to the insanity of war. He achieves that not only with the soundtrack but with the grimy, fog-filtered look, the distracted zoom lens, the abrupt cutting. The film cemented Altman's mature style, which would teeter between thrilling spontaneity and sloppy carelessness for the next couple of decades. Its unexpected success also paved the way for his experiments through the rest of the '70s (not to mention the series which would eclipse it, much to Altman's chagrin). Until his '90s comeback and late-life veneration, M*A*S*H remained Altman's most important and well-known - though far from best - film.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)