Not that Altman can be blamed - Cannon's script for Brewster McLeod's Flying Machine is one-note, mean-spirited, and largely pointless. Living in a Manhattan apartment rather than the Houston Astrodome, Cannon's Brewster is a conniving killer obsessed with flight, whose thoughts are heard almost constantly through voice-over. He has two lovers who for whatever reason throw themselves at him while abiding his abuse - a Puerto Rican caricature named Manessa and a nurturing older woman named Louise, who would become Sally Kellerman's de-winged Fairy Birdmother in the film version. He later meets a childhood sweetheart named Susanne, who would be transformed into Shelley Duvall's free-spirited love interest. This Brewster gleefully kills a series of rivals in the screenplay, the deaths finally catching up to him just as he's ready to launch into flight from Eero Saarinen's TWA Flight Center.

Then-film student C. Kirk McLelland hung around the Houston set of Brewster McCloud and published his journal as On Making a Movie: Brewster McCloud, which also contained the shooting script (essentially a shot-by-shot transcription of the finished film) and Cannon's screenplay. McLelland, despite a raft of factual inaccuracies and youthful egotism, captures the loose, unruly atmosphere of the shoot, which fully translates into the on-screen action. Altman has called his films "caprices" in interviews, and nowhere is that spirit more evident than in Brewster McCloud.

If the end result isn't entirely successful, it is in some ways the ultimate expression of Altman's gambling spirit. Each day's filming seems guided by the whim of the moment, a willingness to roll the dice on every wild idea and see what happens. If the director worked more like Mike Leigh, taking the time to take those chances for an extended period before the cameras roll, the end result might be more cohesive - but would lack Altman's seat-of-the-pants spirit.

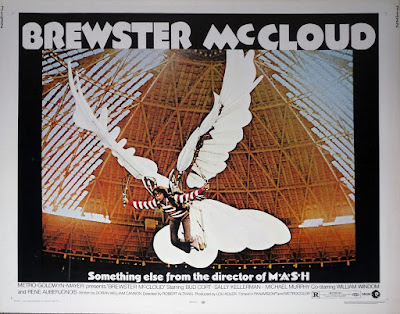

At times the film works beautifully, most notably in Brewster's final flight in designer Leon Erickson's fantastic wing contraption, a breathtaking moment thrillingly shot and edited. Unlike Cannon's tale of a hands-on murderer, Altman's more elliptical approach is far more intriguing, with all the killings happening offscreen, heralded by birdshit hitting the victims, and the culprit left vague - is Brewster committing the crimes or is Louise - or the target-shitting raven? Does Louise even exist, or is she simply some Oedipal projection of Brewster's?

Other aspects suffer from the ever-changing script process. Most glaring is Lt. Frank Shaft's suicide, which comes from nowhere, matters little, and does nothing that Michael Murphy's already deadpan parody of Steve McQueen's Bullitt hasn't already accomplished. Far too much time is spent on the squabbles between opposing factions in the police and politics, which spatters birdshit on low-hanging fruit.

The two halves of the film, which come together in a freewheeling car chase, are thus somewhat at odds with each other, but each adds up to what is essentially a critique of the power structure and its squashing of non-conformity. By relegating the murders to offscreen action and only showing the victims - each venal, corrupt, and largely racist - taking a hit of flyby excrement, Altman suggests that these powerful people deserve to be up-ended by a dreamer and his work.

Still, a line from René Auberjonois' bird-man lecturer tips Altman's hat: "We will... hope that we draw no conclusions," he says regarding his intention to speak on the similarities between birds and men. "Elsewise the subject shall cease to fascinate and, alas, another dream would be lost." Nothing could better sum up Altman's approach, which merrily sacrifices comprehension for the pursuit of the dream.